Leading Asia’s Financial Future – Hong Kong Green Investment Bank (continuation)

Continuation from Leading Asia’s Financial Future Hong Kong Green Investment Bank

Read the paper below:

C. GreenBank’s Role in Hong Kong’s Financial Markets

7| Financing – Generating Large Scale Funding for LCR Infrastructure

GreenBank’s role would be to facilitate large scale funding for LCR infrastructure by making projects more attractive to institutional investors and lenders. Projects funded by GreenBank may include renewable energy and energy efficiency improvements, water and waste management and clean city development (including transportation and municipal construction).

Source: Bloomberg New Energy Finance

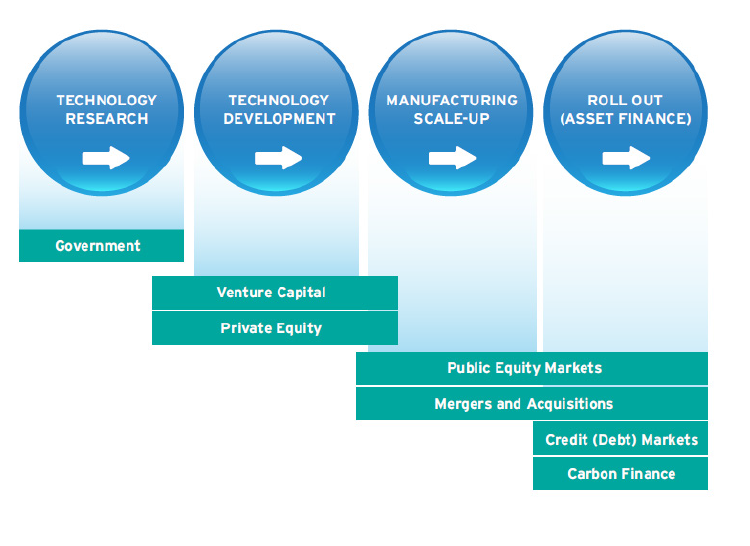

LCR infrastructure, and its underlying technologies, requires financial support along the various phases of its development, from research funding and venture capital for early stage companies, through to asset finance of utility scale projects and operating facilities. Following the model of other GIBs, and given its mandate to maximise private funding, GreenBank would focus on supporting investment in deploying proven commercial technologies, which offer the greatest opportunities for development at scale across new markets. (GreenBank will, however, retain flexibility to consider projects at different phases of maturity on a case by case basis).

GreenBank’s investment activity would utilise the techniques of socalled “blended finance”, which has been successfully employed by multilateral and bilateral development finance institutions for some years to catalyse private investment in emerging markets. In addition to investing its own capital in LCR infrastructure projects, GreenBank would use a range of financial tools to address structural features of projects related to size or risk that currently deter potential investors.

Blended Finance

Blended finance is the strategic use of public or private funds, including concessional tools, to mobilise additional capital flows (public and/or private) to emerging and frontier markets, and represents one approach that has the potential to attract new sources of funding to the biggest global challenges.71

GreenBank would be informed by the experiences of other GIBs, institutional investors, development and financial institutions in building its investment strategy and structuring bankable transactions that maximise private capital. Building on precedents and models that have been successfully executed in a number of markets around the world, GreenBank could consider participating in a rage of potential financing activities, such as those described in the following sections:

7.1 Coinvestment

GreenBank would directly invest in LCR infrastructure in Hong Kong and across Asia – through equity, senior or subordinated debt – in partnership with private investors. If a project is only able to secure financing for a portion of the costs, GreenBank would provide the remaining funds needed to close the deal.

• Project investment

GreenBank may coinvest directly in individual transactions to support development of LCR infrastructure.

Birmingham Bio Power Ltd.

UK GIB formed a consortium with private partners, including Balfour Beatty and several private investment funds, to invest £48 million in a a plant that converts recovered wood into electricity using gasification technology. Over its expected 20 year lifetime, the plant is forecast to supply enough renewable energy to power 17,000 homes each year and to save around 1.3 million tonnes of wood from landfill. UK GIB directly invested £12 million through preferred loan stock and a further £6.2 million in indirect investment through its cornerstone stake in the UK Waste Resources and Energy Investments Fund, one of the coinvestors in the project.72

GreenBank may also invest in alongside public and private sector partners in wider development initiatives, such as urban renewal.

Investing in Clean Cities in Australia

Australia’s Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC) has developed programmes to help city councils manage their energy costs and lower their emissions, through renewable energy, energy efficiency and low emissions technology. For example, CEFC is providing finance to help the city of Melbourne undertake an AUS$30 million programme of clean energy initiatives to help it reduce its energy use and reach a goal of zero net emissions by 2020. The programme will support:

- installation of rooftop solar panels on council and community facilities

- replacement of public lighting with more than 16,000 energy efficient LEDs

- environmental upgrade of commercial properties through the Sustainable Melbourne Fund73

• Fund investment

GreenBank would inject capital into third party funds set up by development institutions or fund managers focusing on LCR infrastructure. GreenBank may act as a cornerstone or anchor investor in a fund early in the investment process so as to play a demonstration role and attract other institutional investors, such as pension and insurance funds.

IFC Climate Catalyst Fund LP

IFC Climate Catalyst Fund, operated by IFC, invests in climate change and resource efficiency projects in emerging markets. Reaching a final fund size of US$418 million in 2014, it is one of the biggest private equity fund of funds focusing on climate businesses in these markets. The UK government was a US$80 million anchor investor. Public sector commitments also came from the governments of Canada and Norway and the Japan Bank for International Cooperation, alongside private institutional investors including Azerbaijan’s sovereign wealth fund and pension funds in Germany and Australia.74

In order to address specific funding gaps in the market, GreenBank may itself establish a fund vehicle that meets the needs of a particular industry or geography.

UK GIB Offshore Wind Fund

UK GIB created the world’s first offshore wind fund to create new capital for an underfunded renewable energy technology which it believed had enormous potential. The fund makes equity investments in operating UK offshore wind power generation assets, and has been instrumental in bringing down the long term cost of finance for offshore wind, as well as enabling the original developers to free up their capital to develop new projects. The fund now has assets under management of over £1 billion. Private investors in the fund include one of the world’s largest sovereign wealth funds, several UK pension funds and a leading Swedish insurance company. Many of them had never invested in wind power previously.75

GreenBank may also work with a commercial financial institution jointly to establish and operate investment fund vehicles.

DB Masdar Clean Tech Fund

DB Masdar Clean Tech Fund was developed by Masdar Capital (part of Abu Dhabi’s GIB) in conjunction with Deutsche Bank. It invests in expansion and later stage companies operating in renewable energy, environmental resources and energy and material efficiency sectors. The fund has attracted a range of public and private investors, including Japan Bank for International Cooperation, Development Bank of Japan, Siemens, Inpex Corporation, Nippon Oil Corporation and GE.76

7.2 Credit Enhancement

GreenBank would attract more private capital for LCR infrastructure at affordable rates through providing credit enhancement for project investments and debt finance. If a private investor is hesitant to enter a new market, or is only willing to offer unnecessarily high interest rates, credit enhancement – or derisking investments for private investors – can provide security and improve deal economics for the project developer. Risk mitigation allows investors to participate in projects on reasonable terms and thereby become more familiar with viable LCR infrastructure markets.

Credit enhancement can be provided via a range of structures, such as loan loss reserves, first loss equity tranches, guarantees or insurance, which GreenBank would tailor to fit the needs of a specific project. In addition, GreenBank may provide support to a transaction which enables investors to offer better financing terms to the project developer, such as more competitive funding rates or longer repayment periods.

- GreenBank’s presence as a lender or investor may itself give confidence to other international funders to participate in a transaction.

Burgos Wind Power Corporation

ADB participated in the financing of the largest wind farm in the Philippines in 2015. ADB’s loan of US$20 million helped to facilitate the total funding package of around $450 million, including participation by a syndicate of international commercial banks. ADB’s credit report on the project stated: “ADB’s involvement and strong relationship with the government will provide comfort to international investors, increase commercial bank participation, and help ensure the government’s long term commitment to the sector”.77

- GreenBank would use financial tools to reduce investors’ exposure to one or more risks involved in a project, which would otherwise prevent them from providing funding. These risks could be project specific, such as technology without a long operating track record or local companies with limited experience, or could be related to cross border issues, such as currency risk.

Hedging Currency Risk in India

Inability to take currency risk often deters foreign investment in low carbon projects, and costs of hedging products can be high. Foreign currency denominated investments are one option, but may limit borrowers’ ability to service their debts. Targeted hedging facilities, such as the Indian Currency Hedging Facility proposed by the Climate Policy Initiative, can potentially offer lower cost and longer term hedging solutions specifically targeting low carbon infrastructure.78

- GreenBank could use targeted insurance products to crowd in private investment and demonstrate the attractiveness of investments to lenders in new sectors. Insurance products, such as those offered by the US’ Overseas Private Investment Corporation79 to facilitate cross border investment and financing for projects in emerging economies, are well established in international markets. GreenBank could work with public or private sector insurance partners to develop products that target low carbon and climate resilient sectors.

Energy Savings Insurance

The Energy Savings Insurance (ESI) tool, developed by the Inter American Development Bank, works with local banks to offer insurance products to boost SME energy efficiency lending in Latin American countries. Cover is provided for projected energy savings for specifically defined and verifiable actions agreed upon in a standard contract between SMEs and energy efficiency services and technology providers. The ESI programme also includes targeted training for banks, borrowers and contractors in their local markets.80

- GreenBank could offer guarantees, which are another well known risk enhancement product used to facilitate cross border investment. Development banks and multilateral agencies such as the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (part of the World Bank81), as well as national level entities, are active in providing guarantees to cover particular risks of transactions in emerging markets.

Private investors often have high perceptions of the policy and regulatory risks in infrastructure projects combined with serious concerns about the technology risk of low carbon sectors. GreenBank would design guarantees to target these specific classes of risk and encourage their participation. As more low carbon projects are completed, a growing track record will generate new data, shape perceptions of risk and help to build investor comfort with the sector.

China Utility Based Energy Efficiency Finance Programme (CHUEE)

IFC established its CHUEE programme to support energy efficiency and clean energy lending by Chinese banks. The key financial mechanism under the programme was a risk sharing facility whereby IFC guaranteed a part of any losses on loans made by the banks. IFC also provided technical expertise and support for financing, marketing, engineering and project development. Since inception in 2006, the CHUEE programme has supported nearly US$800 million of local lending.82

- GreenBank’s support for a transaction or new financial product may enable the end user to access better financing terms, such as more competitive funding rates or longer repayment periods. This would reduce costs or increase the return on an investment, which creates a greater incentive for the project to proceed.

Green Loans, Netherlands

Three Dutch banks, ING Groenbank, ASN Groenprojectenfonds and Triodos Groenfonds, agreed a €100 million loan to Eneco, a Dutch energy company, in order to finance around 50 renewable energy projects. The loan was covered by the the Regeling Groenprojecten scheme, a public private arrangement created in 1995 by the Dutch government, under which certified “green loans” are provided at a lower interest rate.83

CT Green Bank’s Smart E-Loan

CT Green Bank’s “Smart E-Loan” is a second loss loan reserve standard offer made available to any bank or private lender in the state, whereby CT Green Bank guarantees a portion of any potential loan defaults. In exchange, the lenders make capital available at better rates for residential home energy upgrade loans, which can be used for renewable energy and energy efficiency. The availability of financing with lower rates and longer terms enables borrowers to make more substantial improvements to their energy infrastructure.84

- Bonds are often issued to refinance the up front development costs of LCR infrastructure assets, after the typically more risky construction phase is completed. If a project or market is still perceived as high risk by international investors, a GreenBank risk “wrapper” could be provided to achieve a successful financing on reasonable terms in Hong Kong or other international capital markets. (Companies with a strong credit rating that can access the bond markets on attractive terms do not need GreenBank support).

Tiwi-MakBan Geothermal

ADB provided credit enhancement in 2016 to AP Renewables Inc for the issuance of a US$225 million project bond to finance its Tiwi-MakBan geothermal energy facilities in the Philippines. ADB will guarantee 75% of principal and interest on the bond, which is denominated in local currency. The transaction was Asia’s first certified climate bond.85

7.3 Aggregation and Securitisation

Small and geographically dispersed projects, such as off grid power or residential energy efficiency projects, often struggle to raise financing because, by their nature, the projects are relatively low cost and may differ in terms of credit, technology and location. High transaction costs and time required to analyse the projects often deters investors and lenders.

GreenBank would play a role in aggregating these smaller projects into a single entity. By vetting the projects to diversify risk and achieve scale, GreenBank would create a vehicle that is more likely to be attractive to private funders. The bundled assets can then be refinanced by sale to new banks or investors or through securitisation in the capital markets. By increasing the ability of LCR infrastructure projects to access finance, GreenBank would not only lower their cost of capital, but also increase the liquidity of project developers, allowing them to put capital back into developing new projects.

CT Green Bank’s C-Pace Programme

Connecticut has implemented one of the most successful commercial building energy efficiency programmes in the US, using the Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) structure, which allows building owners to receive long term financing to perform energy upgrades on buildings and pay the loan back as a new tax lien on the property. CT Green Bank’s C-PACE programme provides a standardised approach for all commercial PACE deals in the state, allowing for greater scale. The programme was launched in early 2013 and in its first two years CT Green Bank financed nearly US$65 million in energy upgrades for more than 90 buildings.86

Creation of asset backed securities (ABS) is already a familiar process in the Hong Kong capital markets, where transactions are backed, for example, by residential and commercial mortgages and by toll facilities.

Bauhinia Mortgage Backed Securitisation Programme

The Bauhinia Mortgage Backed Securitisation Programme was established by HKMC to promote the development of the mortgage backed securities market in Hong Kong. Under the programme, HKMC sells mortgage loan portfolios to a special purpose vehicle, which then issues ABS for sale to investors. Bonds can be issued under the programme in multiple currencies via both public issues and private placements.87

In China, asset securitisation has also expanded rapidly as the government looks to increase liquidity without expanding the money supply. China’s banking regulator, China Banking Regu- latory Commission, has been recently considering the launch of ABS based on loans to “green industries”.88

GreenBank could facilitate the development of a green ABS market in Hong Kong on the same basis. This would allow for securitisation of loans to LCR infrastructure or green businesses which are currently on the balance sheets of local banks. These sectors typically form a very small part of a bank’s loan book, and its ability to extend capital is therefore limited.

Selling these assets to a GreenBank vehicle would free up the bank’s balance sheet and allow it to recyle its capital – to lend to more projects in green sectors. It would also remove the requirement for the bank to make provision against long term loans on its books and mean it is less likely to hit its prudential limits on single borrowers and sectors. The reduction of these constraints creates greater liquidity for banks and may encourage them to increase portfolio lending allocations to LCR infrastructure and green businesses.

SolarCity Asset Backed Securities

Solar energy company SolarCity issued the first solar ABS in the US in 2013. SolarCity is the largest installer of residential solar in the country, and the US$54 million deal was underpinned by lease payments mostly from its residential customers. Since then, it has issued another two rounds of ABS backed by power purchase agreements from its customers. All have received an investment grade rating of BBB+.89

FlexiGroup Solar Securitisation

In 2016, Australian FlexiGroup Ltd issued a green ABS deal of AUS$50 million with proceeds allocated to refinancing of residential rooftop solar PV systems. The green bond is certified against the Climate Bonds Standard, providing third party verification of the deal’s green credentials.90 A second certified solar securitisation followed in February 2017. Both issuances received a AUS$20 million cornerstone investment from CEFC.

GreenBank could also provide credit enhancement to a pool of securitised assets underlying a bond issue, in order to enable it to gain an investment grade credit, which is the minimum requirement for many institutional investors to consider buying the bonds.

New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA)

NYSERDA issued a US$26 million bond in 2013 to securitise a portfolio of residential and small commercial sector energy efficiency loans. Because the underlying loans were all relatively new, there was limited data on the payment performance of the portfolio to be rated. Credit enhancement was needed to earn an investment grade rating that would allow institutional investors to purchase the bond. NYSERDA was able to secure federal tax benefits and worked with New York State’s Environmental Facilities Corporation, an AAA issuer, to structure the transaction in a way that met the needs of investors.91

7.4 Warehousing

In the event that no private lender is willing to make loans to a certain market, GreenBank could originate and finance its own clean energy projects. This situation may arise if a given clean energy technology itself is perceived as too risky, if the market segment is viewed as having high credit risk or if the investments themselves are too small or not cost effective to underwrite.

In addition to acting as an intermediary to identify, vet and aggregate smaller projects, GreenBank would underwrite loans to a pool of projects directly and “warehouse” them (hold them on its own balance sheet) until sufficient scale is reached to make the portfolio attractive to institutional investors. GreenBank would later sell the loans to private investors through private placement or securitisation, replacing its own capital with private funding.

Warehouse for Energy Efficiency Lending (WHEEL)

WHEEL is a cross state energy efficiency financing platform launched in the US to attract institutional investors by achieving scale through aggregation of projects and consistency through project standardisation. WHEEL utilises a pool of capital provided by Citibank, made available to any state that provides a credit enhancing mechanism into the warehouse. Citibank and its downstream partners provide funding through a contractor network for home energy upgrades. New York Green Bank (NY Green Bank) entered the scheme by making a US$20m subordinated investment, which has unlocked US$100m of loan capital for New York state residents.92

C-PACE Refinancing

CT Green Bank initially acted itself as the originator and underwriter of loans under its PACE programme as no commercial bank was willing to be the first to invest under the untested structure. CT Green Bank sourced deals for aggregation into a portfolio until loan performance had been demonstrated at sufficient scale. CT Green Bank later sold 80% of the loan portfolio through an auction to a specialty finance company, Clean Fund.93 This initial success proved the viability of the market to private investors, and in December 2015 Hannon Armstrong, a private investment trust, committed US$100 million to finance further C-PACE projects in Connecticut.94

8| Market Development – Fostering a Green Finance Industry in Hong Kong

GreenBank would play an important role in developing the market for green finance in Hong Kong, by building capacity for investment in LCR infrastructure among local banks, institutional asset owners and fund managers and coordinating activities of government agencies, HKEx and industry associations.

GreenBank would accelerate the development of a market ecosystem around green finance, leading to higher levels of expertise within financial institutions and innovation in design of tools and financial products to support LCR infrastructure investment.

Given its status as a public institution, GreenBank would also have direct access to policy makers in Hong Kong and would be well positioned to understand government goals and priorities for infrastructure development, including with regard to Belt and Road and the Greater Bay Area, which could highlight opportunities for its own project pipeline. GreenBank would also be able to discuss structural issues that potentially constrain investment in LCR infrastructure, including regulatory barriers such as ratings hurdles or liquidity requirements for institutional investors.

8.1 Hub for Information, Training and Capacity Building

GreenBank would provide a central hub for information on the value, risks and processes involved in deploying and funding LCR infrastructure. It would provide a platform for companies and financial institutions to increase their competencies in these sectors, share experiences and understand international best practice.

• Information

- GreenBank would hold information on companies providing goods and services for deployment and financing of LCR infrastructure, including technical specialists, such as energy service companies (ESCOs) and consultants: for example, monitoring and verification experts.

- GreenBank would gather data from developers, contractors, rating agencies and financial institutions on opportunities and barriers to investing in LCR infrastructure. It would share information with local industry associations such as the Hong Kong Association of Banks and the Hong Kong Investment Funds Association, as well as the IFFO and AIIB.

- GreenBank would convene local market participants and international regulators, institutional investors and funders to discuss best practice and develop processes for collaboration. GreenBank would invite participation of global networks such as the International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds, the Long Term Infrastructure Investors Association and the Association of Development Financing Institutions in Asia and the Pacific, as well as other global GIBs.

- GreenBank would centralise information on government programmes supporting LCR infrastructure development in Asia. Incentives include subsidies, rebates, loans, technical assistance and green procurement programmes, but support and information tends to be located in multiple agencies and utilities, making it difficult for companies to access them and constraining consumer demand.

• Training and capacity building

- GreenBank would support the provision of technical assistance, capacity building and training for financial institutions, building contractors and supply chain companies to increase the levels of skills with green finance across the market.

- GreenBank would support project preparation activities, particularly in emerging markets where developers (including host governments) may lack expertise and have limited development financing. In the early preparation phases of projects, expert input and technical assistance can be critical to producing the necessary feasibility studies, research on new sectors or project types and strategic plans.

- Where appropriate, GreenBank would identify third parties to provide capacity building and skills development. GreenBank would also encourage professional organisations to include green finance in their own training activities in Hong Kong and to incorporate it into “continuing professional development” for market participants.

Professional Qualifications

Analysis of environmental risk is being integrated into the syllabuses of several professional financial qualification organisations in the UK, including the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales, the Chartered Banker Institute, the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants and the Chartered Institute for Securities and Investment.95

- GreenBank would encourage greater understanding among government departments of the opportunities for developing and funding LCR infrastructure, and seek to encourage government agencies to collaborate on finding solutions to constraints on investment, including the need for clearer, consistent policy signals, revising legal frameworks and removing negative incentives (such as fossil fuel subsidies).

8.2 Channel for Global Collaboration

GreenBank would provide a central contact point for international providers of capital, both public and private sector.

• International capital providers

- GreenBank would encourage participation by multilateral and national development banks and other sources of public climate finance96 in its financing and risk enhancement activities. These institutions control a large pool of public capital, contributing nearly US$150 billion in annual climate finance flows alone.97

European Investment Bank (EIB)

The EIB is the European Union’s development bank and the largest supranational borrower and lender in the world. EIB financing in Asia has reached €7.1 billion, two thirds of which is deployed in China and India. EIB has supported a broad range of projects in the region, including climate change mitigation, renewable energy and energy efficiency, water and wastewater and support to SMEs.98

Many of these public institutions have a high level of experience with LCR infrastructure investment in Asia and, in particular, blended finance techniques. They offer a wide variety of support mechanisms. However, identifying specific programmes and understanding which institutions may be the most appropriate partners can be extremely onerous for private actors. GreenBank would act as a conduit for structuring suitable projects with multiple participants and bringing together offshore and local funders.

Climate Finance Funds

The OECD’s Climate Fund Inventory database lists 99 bilateral and multilateral public climate funds existing to support countries with their climate change mitigation and adaptation actions. These funds target different fields of activities and different geographies and they enable support via multiple financing mechanisms.99

• Global financial market development

- GreenBank would participate in relevant international efforts by financial centres to align green standards and exchange ideas and expertise. The establishment of guidelines (both technical and financial) across markets which create greater consistency and transparency is likely to help to increase private sector appetite for LCR infrastructure.

A number of initiatives are well established, such as the Sustainable Stock Exchange project, of which HKEx is a member100, and the Sustainable Banking Network. Several of the global GIBs are members of the Green Bank Network.101

Sustainable Banking Network (SBN)

SBN is a community of financial sector regulatory agencies and banking associations from ten emerging markets committed to advancing sustainable finance in line with international good practice. SBN supports them in policy development and related initiatives to create drivers for sustainable finance locally. To date, 15 countries have launched national policies, guidelines, principles or roadmaps focused on sustainable banking, including China, Bangladesh, Indonesia and Vietnam.102

8.3 Promoting Standardisation and Transparency

GreenBank would emphasise the importance of replicability and standardisation. It would seek to focus on projects which (once the project model has been designed and proven) can be repeated relatively easily so that funding can be scaled up rapidly. It would also encourage greater conformity of processes, contracts and data collection, in order to lower transaction costs and help to encourage private sector participation in LCR infrastructure projects.

• Standardisation

- Substantial liquid markets have been created for financing industry sectors, such as home mortgages and auto loans, that have broadly standardised their contract language and underwriting processes, thus reducing cost and uncertainty in the lending process. GreenBank would seek to initiate and develop industry standards for LCR infrastructure sectors that deliver similar benefits.

Standardisation would make it easier and cheaper for securitisation to occur, for banks to underwrite and for credit agencies to rate a securitisation. In addition to loan documentation, standardisation of project contracts such as offtake agreements, energy savings contracts and lease agreements would ease the complexity of executing projects, as would standardised data collection on loan and project performance.

National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL)

NREL, a government laboratory in the US focusing on development and deployment of renewable energy and energy efficiency technologies, hosted the Solar Access to Public Capital working group of industry participants for several years. The group working on development of standardised power purchase agreements and related documentation for distributed solar projects, in order to increase the flow of private capital to this market.103

- GreenBank would aim to emulate successful market led efforts to establish common standards such as the IFC’s Equator Principles and the Green Bond Principles coordinated by the International Capital Market Association.104 It would collaborate with HKEx, ratings agencies and other market participants to develop appropriate methodologies.

Equator Principles

The Equator Principles is a risk management framework, adopted by commercial financial institutions, defining roles and responsibilities of lenders and borrowers in determining, assessing and managing environmental and social risk in project finance. As of August 2016, 84 financial institutions in 36 countries have officially adopted the principles, representing over 70% of international project finance debt in emerging markets.105

Luxembourg Green Exchange (LGX)

LGX was launched in 2016 to be a dedicated platform for green, social and sustainable securities, where they can market their instruments and publish information relating to the use of proceeds, both at the start and during the lifetime of a security. Only issuers that commit to entry requirements and provide full transparency on their projects can be displayed on LGX. Over 130 green, social and sustainable bonds are displayed on LGX currently, representing a total volume of €57 billion.106

• Transparency

- GreenBank would work with regulators and market participants to push for consistent labelling of green financial products through the development of industry guidelines covering information to be provided in product prospectuses and marketing documents, as well as common performance metrics for green impacts and established methodologies, approaches and verification procedures for their calculation.

- GreenBank would collaborate with market participants, academic institutions and NGOs to study the investment performance and risk profile of green finance instruments and disseminate the findings publicly.

Institute for Market Transformation (IMT)

IMT, a think tank based in the US, in 2013 published a study on financing of energy efficiency measures in homes. A review of over 70,000 home mortgages found that default risks were 32% lower on average in energy efficient homes, controlling for other loan determinants, and that the owner was 25% less likely to prepay the mortgage. IMT suggested that the lower risks associated with energy efficiency should be taken into consideration by banks when underwriting mortgages.107

- GreenBank would disclose the financial and non financial impacts of its own investments, together with the principles and methodologies it employs for assessing them. This could provide a template for private investors looking to evaluate LCR infrastructure.

Green Investment Handbook, UK GIB

The Green Investment Handbook is a manual that explains how UK GIB quantifies and reports on the environmental benefits of its investments. It provides guidance on how it measures green performance, manages risk, conducts due diligence and engages consultants. It sets out a consistent means of assessing, monitoring and reporting performance, and suggests practical tools and best practice methodologies to support the large scale mobilisation of climate finance. The handbook has been translated into several languages.108

8.4 Product Design

GreenBank would be a centre for designing, piloting and demonstrating innovative financing approaches and new business models to address specific challenges of LCR infrastructure investment.

- GreenBank would encourage local market participants, together with foundations, NGOs, academia and think tanks, to develop new market solutions, for example:

- specialised ratings for low carbon and climate resilient projects

- commercial credit enhancement such as monoline insurance

- flexible public private guarantee structures or hedging mechanisms.

- If necessary, GreenBank would itself develop solutions to fill gaps in the market where financial tools for financing LCR infrastructure do not currently exist on a commercial basis. GreenBank would be well positioned to coordinate multiple industry partners (such as utility companies), financial institutions (banks and insurers) and government departments to deliver turnkey solutions to businesses and consumers. New financing structures may need a significant amount of upfront political support and administrative effort, but once they are established the role of GreenBank could be scaled back.

- GreenBank would also collaborate with global initiatives seeking to develop innovative financing approaches for LCR infrastructure. Tools that have been proposed or are under development elsewhere could be tested, implemented and potentially scaled up by GreenBank.

Global Innovation Lab for Climate Finance and Financing for Resilient Investment (the Lab)

The Lab is a global forum charged with taking G7 endorsed green finance projects “from talk to action”. It convenes international experts to design, stress test and pilot instruments and approaches that might catalyse private investment in climate friendly, low carbon projects and infrastructure in developing countries. The Lab’s first call for proposals attracted 80 submissions worldwide.109

- GreenBank might experiment with offering “challenge prizes”, which are offered as a reward to whoever can first or most effectively meet a defined challenge associated with scaling up private financing for LCR infrastructure.

Virgin Earth Challenge

The Virgin Earth Challenge was launched in 2007 to find sustainable and scalable ways of removing greenhouse gases from the atmosphere. It offers a reward of US$25 million for the most successful solution. The project received over 10,000 applications and 2,600 formal proposals, which have been reduced to 11 finalists.110

8.5 Support for Early Stage Green Innovation

Although GIBs typically invest in deploying proven commercial technologies, GreenBank would retain the flexibility to invest in new technologies or innovative financing techniques that have potential to encourage appetite for LCR infrastructure development or future investment.

- GreenBank could selectively invest in early stage companies or technological development or could selectively support R&D in Hong Kong universities. Investments may be made in collaboration with Hong Kong government programmes supporting innovation, such as the Innovation and Technology Bureau.

Clean Energy Innovation Fund

Australia’s CEFC works with the Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA), which facilitates technologies progressing from early stage research through to commercialisation by supporting the research, development and demonstration stages. In 2016, the government launched the AUS$1 billion Clean Energy Innovation Fund, jointly managed by CEFC and ARENA, which will provide early stage and growth capital for clean energy companies and projects.111

- GreenBank could identify opportunities to introduce technology that has a track record elsewhere to new markets in Asia, which might create significant potential for deployment at scale.

Archimedes Screw Turbine Technology

CT Green Bank financed the first installation of a new hydropower technology, the Archimedes screw generator, which turns slowly to allow fish to pass through. The technology had been deployed in Europe for several years, but not yet introduced to the United States. The project was financed together with three commercial banks as coinvestors in a green bond.112

- GreenBank could collaborate with relevant experts to explore emerging and alternative sources of financing for LCR infrastructure, including potential linkages between green finance and financial technology.

ANT Financial’s Green Energy App

In 2016, ANT Financial launched a “green energy” app that rewards users for reduced carbon use, revealed through a set of algorithms that translate an individual’s financial transaction data into an estimate of his carbon footprint.113 Purchases made through its Alipay payment platform are tracked to earn “green energy points” in the Ant Forest Programme. In the first nine months after introduction, some 200 million subscribers are using the app.114

- GreenBank could also collaborate with relevant experts to explore methods of scaling up retail investment in LCR infrastructure: for example, by partnering with crowdfunding investment platforms.

Abundance

Abundance in the UK is a green crowdfunding platform, allowing small investors to put money into UK renewable energy schemes. Established in 2012, the platform has raised almost £54 million to help fund 27 projects. In 2016, Abundance supported the UK’s first local authority solar bond, raising £1.8 million for a partnership between Swindon Borough Council and the local community.115

D. Setting Up and Operating Greenbank

9| Strategy for Success

GreenBank’s effectiveness would be largely driven by its dedicated mission – scaling up private financing for LCR infrastructure in Asia. This clear focus would ensure that GreenBank would not be distracted by competing investment agendas (unlike a typical development bank, which has to tackle broader poverty alleviation and societal improvements). It would also insulate GreenBank from pressure to support alternative economic targets or to dilute its resources across multiple industry sectors.

GreenBank’s specific mandate would also allow it rapidly to establish its presence and reputation in the LCR infrastructure financing arena, and to attract specialised expertise, both by hiring an appropriately qualified team and by establishing relationships with its peers across the region and internationally.

9.1 Structure and Governance

GIBs have been created in a number of ways, including through government directive, administrative action or the passage of new legislation. For GreenBank to be able to operate, it would require116:

- A legal presence as a defined organisation

- Capital to invest or lend and to cover operating expenses

- Strategic focus and authority to perform a specific set of financing activities

• Legal presence

GreenBank may be established as a new entity or created out of an existing institution.

Global GIBs – Organisational Structures

In some cases, GIBs have been newly formed institutions. In others, they have consolidated existing programmes under one entity or converted an existing entity into a GIB. For example, UK GIB, CEFC and Japan’s GFO were created as new entities, but CT Green Bank was created by transferring existing programmes into a new entity, while GreenTech Malaysia and NY Green Bank were created as divisions or subsidiaries of existing institutions.117

There are a number of arguments for GreenBank having the status of an independent entity:

- Creation of a new entity would maximise its GreenBank’s global impact. A dedicated entity provides a clear point of contact for financing for certain types of activities, which is easily understood by market participants.

- Operating GreenBank as a stand alone entity would highlight its commitment to its mandate and allow it to be more organisationally focused on its targeted objectives than if it were a programme area of an institution already focused on other activities.

- Establishing GreenBank as a separate institution would emphasise to the market that it is independent and will not be influenced by political pressure or interference.

The creation of GreenBank as a separate entity, however, may incur costs, complexities and political delays. In order to implement the policy in the shortest possible time scale, it may be appropriate to consider establishing GreenBank as a division of the HKMA or another Hong Kong government agency.

• Organisational independence

Even if GreenBank were set up as a division of a government agency or department, it would be essential that it have organisational independence, which allows it to maintain its operating focus, regardless of potential political shifts, budget changes and administrative priorities.

It must be clear to the markets that there would be no government interference in the investment decision making of GreenBank. (Approval of individual investments by politicians may create the perception that GreenBank is merely supporting pet projects, rather than focusing on market needs). In order to attract private sector actors as partners in its projects, committing long term capital, GreenBank would need to demonstrate that its strategy and policy direction is consistent and reliable.

GreenBank’s governance would depend on its legal form, but would at a minimum include a board of directors or an investment review committee that is not appointed directly by government or subject to political influence. The size, composition, terms, selection process and responsibilities of the board or committee would be publicly disclosed in order to provide reassurance to the market of its independence and the competencies of its members.

UK GIB – Governance

UK GIB was created as an entity owned by the British government, but operating as a separate institutional unit at arm’s length and with full operational independence. UK GIB’s corporate board and its committees were expected to operate in line with best practice private sector corporate governance guidelines. The board’s main task was to help set strategic priorities and ensure UK GIB was operating in line with its mission, operating principles and strategy.118

9.2 Capitalisation

GIBs have primarily been capitalised with government funds, either through raising new capital or reallocating existing funds. Unlike typical government programmatic expenditure, funds allocated to a GIB will not be fully used up, leading to a need for replenishment in the next financial year. Instead, public funds are recycled and preserved, so that they can be applied to build up a capital base in the GIB. During the GIB start up period, however, operating losses may be expected and additional funding could be allocated for this purpose.

Global GIBs – Funding Sources

Governments have capitalised GIBs using a variety of funding sources, in addition to general public funds:

- Carbon tax revenue (Japan)

- Emissions trading scheme revenue (Connecticut)

- Utility bill surcharges (New York)

- Appropriations (Australia)119

• Hong Kong Government funding

GreenBank would be initially capitalised with government funds. This could take the form of a single, upfront injection of public funds, or GreenBank could receive government capital over a set number of years, with no more funding after that period.

Rather than capitalising GreenBank fully out of the general public budget, it might be possible to derive part of the funding from alternative government revenue sources. For example, GreenBank might receive funding from Hong Kong building tax revenues or environmental levies. In the future, it might be funded out of potential emissions trading or carbon tax revenues.

A number of governments around the world have implemented creative one off or ongoing revenue raising measures to fund major policy initiatives, in particular the establishment of sovereign wealth and public pension funds.

Australian Future Fund

The Australian Future Fund was created in 2006 by the Australian government as a sovereign wealth fund to meet its future liabilities for the payment of pensions to retired civil servants. In addition to funding out of the general government budget, income from the partial privatisation of Telstra Corporation, a publicly owned telecommunications company, was deposited into the fund. The government also transferred its remaining 17% stake in Telstra into the fund. 120

• International Public Funding

It may be possible to explore additional funding for GreenBank from multilateral and bilateral development finance institutions and climate funds. The mandates of these institutions include targets to scale up green investment in emerging markets, and GreenBank could be a valuable partner for them in developing Asia. The largest global climate funds, such as the Global Environment Facility and Green Climate Fund, have the capacity to support and capitalise GIBs.121

Green Climate Fund (GCF)

The GCF is a global fund established by the UN following the Copenhagen climate negotiations to help developing countries limit or reduce their greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to climate change. Funding of at least US$100 billion per year has been agreed to be channelled through the GCF to promote low emission and climate resilient development. The GCF works directly with public and private financial institutions funding sustainable development in emerging markets. 122

• Capital Markets

Several GIBs, such as CT Green Bank, have issued bonds in the capital markets. These have typically been used to refinance bank loans once project or portfolios have an operating track record and to sell assets through securitisation.

Hawaiian Green Energy Market Securitisation (GEMS) Programme

Hawaii’s GEMS programme issued US$150 million in bonds to fund part of its initial capitalisation. The bond will be repaid using funds from an existing consumer surcharge on electricity bills in the state. Issued in 2014, the AAA rated GEMS bond was able to access low cost capital that is off balance sheet and therefore does not impact the state’s budget.123

GreenBank is likely to issue project bonds and potentially to issue general obligation bonds to raise capital for itself. GreenBank’s status as a government linked entity, and its consequently strong credit rating, would allow it to be partially recapitalised via bond issuance. Capital raised could be used to invest in further projects or returned to the government.

9.3 Strategic Focus

Within its mandate to scale up private financing for LCR infrastructure in Asia, GreenBank would define its strategic focus in terms of industries and technologies it seeks to support and the specific set of financing activities it will perform.

• Financing and investment strategy

- GreenBank would require the authority needed to operate as a financing mechanism in the market, with the ability to invest, lend, guarantee and otherwise structure funding into projects. GreenBank would require a high degree of flexibility with regard to the financing activities it is authorised to carry out. For example, market development activities might require it to supply limited grant or concessional financing.

- Like all financial institutions, GreenBank would be governed by appropriate liquidity and capital standards to enable it to meet its financing obligations, adequately withstand losses and ensure the viability of its operations. Within the parameters of acceptable risk, GreenBank would not be constrained in terms of projects, markets and technologies it could support.

“An investment strategy that is too risk averse would not allow the CEFC to fulfil its mandate, statutory objective and public policy purpose. On the other hand, an approach which is too tolerant of investment risk could lead to higher than acceptable capital losses.”

Clean Energy Finance Corporation, CEFC Investment Policies 2016124

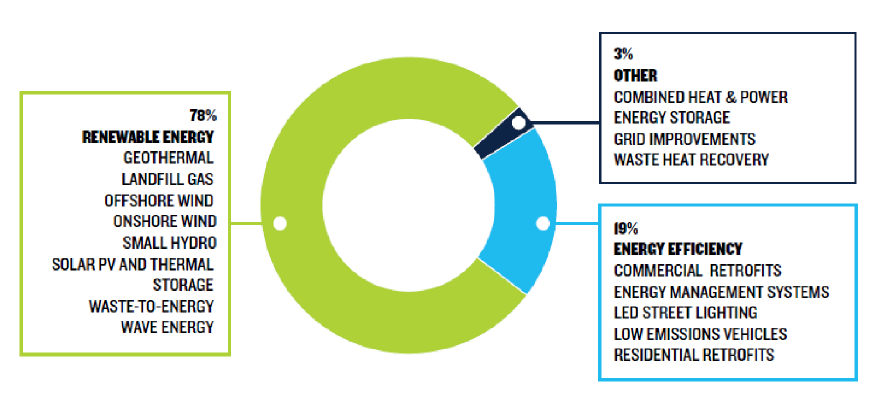

• Identification of target technologies and industries

- The definition of “green” can vary among GIBs, but most have initially focused on renewable energy and energy efficiency, and have sought to send a signal to the markets that their funding seeks out investments that are climate friendly. GreenBank would make its own definition of LCR infrastructure and identify specific technologies that are eligible.

Areas of Investment by Green Bank Network Members125(end of first quarter 2017)

Source: Natural Resources Defense Council, National Development Banks and Green Investment Banks, 2017

- GreenBank may also support selected climate resilience or adaptation projects that are particularly relevant for Hong Kong’s circumstances as coastal city, housing valuable property and business assets and vulnerable to violent weather events.

Energy Resilience Bank (ERB)

The state of New Jersey created the Energy Resilience Bank (ERB) in response to Hurricane Sandy, which caused long lasting power outages throughout the state. The ERB has limited its target market to key infrastructure such as hospitals and water facilities, and made only resilient technologies eligible for investment (for example, energy storage and fuel cells). The ERB offers a blend of low cost capital and grants, while still seeking to leverage private investment. Grid resiliency is an urgent need in New Jersey, so the ERB is flexible with regard to return on its capital in order to attract investment more rapidly.126

• Geographical diversification

- GreenBank would provide financing for LCR infrastructure both locally and throughout Asia. Its ability to invest across the region would be balanced by appropriate concentration limits and portfolio diversification standards.

UK Climate Investments LLP

UK Climate Investments is a joint venture announced in 2015 by UK GIB and the UK Department of Energy and Climate Change. The £200 million fund will target East Africa, South Africa and India and will make minority equity investments in renewable energy and energy efficiency projects.127

• Continuously evolving strategy

- As markets for particular technologies become more liquid and investment conditions in individual emerging countries strengthen, GreenBank’s strategic priorities would shift focus into new technologies and markets.

“NY Green Bank focuses on opportunities that create attractive precedents, standardised practices and roadmaps that capital providers can willingly replicate and scale. As funders “crowd in” to a particular area within the clean energy landscape, NY Green Bank moves on to other areas that have attracted less investor interest.”

New York Green Bank Business Plan 2016128

9.4 Measuring Performance

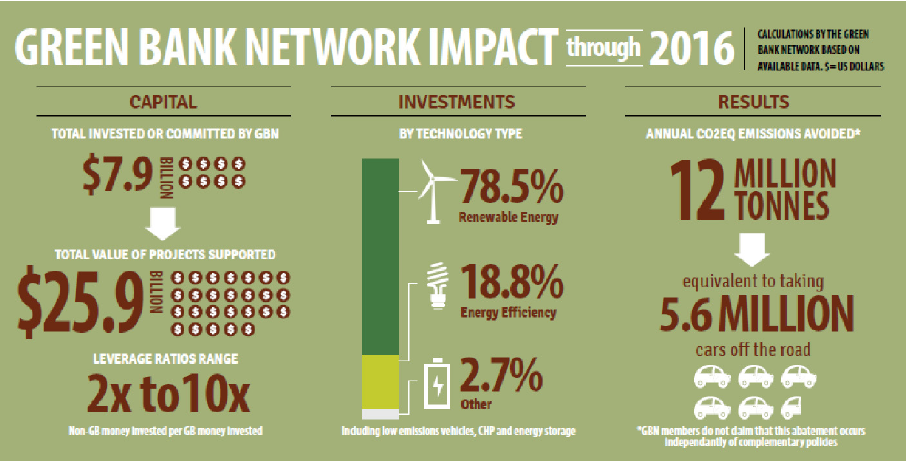

GIBs typically measure their performance using a range of metrics which generally focus on investment and economic results, together with environmental outcomes. Common metrics include:

- Investment: total public capital invested, private capital invested, private to public leverage ratio, return on capital

- Social: clean energy deployed, jobs created

- Environmental: energy generated or saved, emission reductions

Source: Green Bank Network

• Investment metrics

- A primary motivation for the establishment of GreenBank would be to stimulate innovation in Hong Kong’s financial industry and to generate additional activity and revenues for financial institutions and businesses in the city. Measurement of the numbers of local financial institutions participating in transactions and the volume of private sector investment catalysed by GreenBank would demonstrate its role in market development.

- GreenBank’s “leverage ratio” (the amount of private capital that is deployed for each dollar of public investment) would be a key metric for gauging the efficiency and cost effectiveness of the activities it undertakes.

- GreenBank would be expected to break even and eventually to make a return on its investments. Transparency on its financial performance would demonstrate its success and help to maintain political support for its operations. It would be important that any return target is set at a reasonable level that allows GreenBank the flexibility to fulfil its mandate – to fill private financing gaps and achieve overall market development (which may require limited activities to be carried out on a non commercial basis).

Global GIBs – Return Targets

Some GIBS have agreed mandated target returns with their sponsoring governments:

• Social and environmental metrics

- GreenBank would provide information on its LCR infrastructure projects by sub sector and will measure the outcomes generated by each project: for example, renewable energy capacity installed, energy intensity reductions achieved, volume of waste materials processed etc.

- GreenBank would track the numbers of jobs created as a result of its financing of LCR infrastructure in the region.

- GreenBank would collaborate with technical or academic experts to measure the impact on air or water pollution or carbon emissions of its LCR infrastructure projects.

9.5 Long Term Success

GreenBank would be judged to be a valuable policy instrument if it:

- Increases the competitiveness of Hong Kong’s capital markets and financial services industry by creating expertise in green finance, encouraging participation and fostering innovation

- Crowds in significant private capital to fund LCR infrastructure, thereby generating incremental business and profits for Hong Kong companies and financial institutions

- Generates positive social and environmental impacts associated with its projects

- Uses public money responsibly and cost effectively to achieve its goals

The ultimate measure of success for GreenBank would be the creation of mature and efficient markets for financing LCR infrastructure which can operate without its direct intervention. Through the activities of GreenBank, financial institutions in Hong Kong would develop greater expertise in these sectors, which would enable them to compete in new and growing markets on commercial terms.

While GreenBank’s market development activities will be ongoing, it is intended that its financial support for any specific infrastructure sector or investment products should be relatively short term in nature. As each sector matures, GreenBank’s project focus would evolve to reflect new circumstances and it would concentrate on technologies with more challenging risk and return profiles.

Over the longer term, once GreenBank has developed a track record of successful projects and is widely recognised as a highly specialised entity, operating largely on a commercial basis, the Hong Kong government may be in a position to review its investment in GreenBank and consider exit strategies.

UK GIB Privatisation

Five years after its establishment, the UK government in 2017 agreed to sell UK GIB to investment firm Macquarie Group in a £2.3 billion deal. UK GIB has stakes in 85 projects varying from windfarms and energy efficient street lighting to biomass and waste to energy plants. The government has provided £1.5 billion in funding to UK GIB since 2012, and for every £1 it has invested, it has attracted another £3 of third party capital. Macquarie, a global leader in financing infrastructure projects, has committed to UK GIB’s target of leading £3 billion of investment in green energy projects over the next three years.133

Refinancing GreenBank in future years through the capital markets would allow the government to regain part or all of its capital. Alternatively, the government could seek to privatise GreenBank and allow it to continue to operate on a stand alone basis as an entirely commercial entity. In addition to capital, private investors in GreenBank could contribute incremental experience in new technologies or financing techniques that would enable GreenBank to broaden and refine its product offering. Its role as a catalyst of Hong Kong market development would remain unchanged.

Endnotes

71 OECD, “Blended Finance,” Paris: OECD, accessed September 23, 2017, http://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-topics/blended-finance.htm. 72 UK Green Investment Bank, “Annual Report 2013,” Edinburgh: UK Green Investment Bank Pub- lishing, June 25, 2013, 1-83. 73 Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC), “CEFC and the City of Melbourne accelerate sustainability initiatives,” Fact Sheet, Sydney: Clean Energy Finance Corporation, October 2015. 74 Maya Ando, “IFC Catalyst Fund completes $418 million in fundraising,” Asia Asset Management, July 11, 2014, accessed September 22, 2017, http://www.asiaasset.com/news/IFC_Catalyst_Fund_completes_418_million_in_fundraising1407.aspx. 75 Green Investment Group, “Delivering value in the UK’s offshore wind market,” accessed September 23, 2017, http://greeninvestmentgroup.com/funds/offshore-wind-fund/. 76 Deutsche Bank – Middle East & Africa, “DB Masdar Clean Tech Fund completes first close,” January 18, 2010, accessed September 23, 2017, https://www.db.com/mea/en/content/937.htm. 77 Asian Development Bank, “Report and Recommendation of the President to the Board of Directors,” Project Number: 48325-001, Asian Development Bank, January 2015, 1-7. 78 Arsalan Farooquee and Gireesh Shrimali, “Reaching India’s Renewable Energy Targets Cost Effectively: A Foreign Exchange Hedging Facility,” Climate Policy Initiative, June 2015, 1-16. 79 Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC), accessed September 24, 2017, https://www.opic.gov. 80 Inter-American Development Bank, “Energy Savings Insurance (ESI),” accessed September 23, 2017, http://www.iadb.org/en/sector/financial-markets/financial-innovation-lab/energy-savings-insurance-esi19717.html. 81 Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency, World Bank Group, accessed September 23, 2017, https://www.miga.org. 82 International Finance Corporation, World Bank Group, “China Utility-based Energy Efficiency Finance Program (CHUEE),” accessed September 23, 2017, https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/0f680e004a9ad992af9fff9e0dc67fc6/Chuee+brochureEnglish-A4.pdf?MOD=AJPERES. 83 ING, “EUR 100 million green loan to Eneco,” ING Newsroom, accessed September 23, 2017, https://www.ing.com/Newsroom/All-news/Features/Features-old/EUR-100-million-green-loan-to-Eneco.htm. 84 Energize Connecticut, “Smart-E Loans,” accessed September 23, 2017, https://www.energizect.com/your-home/solutions-list/smarte. 85] Asian Development Bank, “ADB Backs First Climate Bond in Asia in Landmark $225 Million Philippines Deal,” February 29, 2016, accessed September 21, 2017, https://www.adb.org/news/adb-backs-first-climate-bond-asia-landmark-225-million-philippines-deal. 86 Connecticut Green Bank, “C-PACE Marks Successful First Two Years as CT Property Owners Take Advantage of Program to Finance Money-Saving Energy Improvements,” Connecticut, February 3, 2015, accessed September 23, 2017, http://www.ctgreenbank.com/c-pace-marks-successful-first-two-years-ct-property-owners-take-advantage-program-finance-money-saving-energy-improvements. 87 The Hong Kong Mortgage Corporation Limited, “Securitisation,” accessed September 24, 2017, http://www.hkmc.com.hk/eng/investor_relations/securitisation.html. 88 Engen Tham, “China mulls ‘green’ sector asset-backed securities: regulator,” Reuters, January 19, 2015, accessed September 24, 2017, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-abs-greensector/china-mulls-green-sector-asset-backed-securities-regulator-idUSKBN0KS0M520150119. 89 Beate Sonerud, “SolarCity issues US$200m of retail bonds, maturity ranging from 1-7 years, coupon 2-4%. What a pioneering company! First public solar bond offering in the US, after also doing the first solar securitisation in 2013,” Climate Bonds Initiative, October 16, 2014, accessed September 24, 2017, https://www.climatebonds.net/2014/10/solarcity-issues-us200m-retail-bonds-maturity-ranging-1-7-years-coupon-2-4-what-pioneering. 90 Sean Kidney, “Sunny side up! FlexiGroup issues first Australian green ABS. Proceeds for solar & 5bps pricing benefit for green label! And .. It’s Climate Bonds Certified!,” Climate Bonds Initiative, April 21, 2016, accessed September 24, 2017, https://www.climatebonds.net/2016/04/sunny-side-flexigroup-issues-first-australian-green-abs-proceeds-solar-5bps-pricing-benefit. 91 Robert G. Sanders et al., “Reduce Risk Increase Clean Energy: How States and Cities are Using Old Finance Tools to Scale Up a New Industry,” Clean Energy and Bond Finance Initiative, August 2013, accessed September 24, 2017, https://www.cleanegroup.org/wp-content/uploads/CEBFI-Reduce-Risk-Increase-Clean-Energy-Report-August2013.pdf. 92 Jeffrey Schub et al., “Green and Resilience Banks: How the Green Investment Bank Model Can Play a Role in Scaling Up Climate Finance in Emerging Markets,” National Resources Defense Council, Coalition for Green Capital and Climate Finance Advisors, November 2016, 1-43. 93 Nick Lombardi, “In a ‘Watershed’ Deal, Securitization Comes to Commercial Efficiency,” Greentech Media, May 19, 2014, accessed September 25, 2017, www.greentechmedia.com/articles/read/the-first-known-commercial-efficiency-securitization. 94 Cision PR Newswire, “Green Bank and Hannon Armstrong Partner for Commercial Clean Energy Financing,” December 17, 2015, accessed September 24, 2017, http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/green-bank-and-hannon-armstrong-partner-for-commercial-clean-energy-financing-300194976.html. 95 City of London Corporation, “Globalising Green Finance: the UK as an International Hub,” London: City of London Corporation’s Green Finance Initiative, November 2016, 1-40. 96 Climate finance typically describes financial flows from developed to developing countries for climate change mitigation or adaptation activities. 97 Barbara Buchner et al., “Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2015,” Climate Policy Initiative, November 2015, 1-15. 98 European Investment Bank, “EIB Financing in Asia,” Luxembourg: European Investment Bank, July 27, 2017, 1-2. 99 OECD, “Climate Fund Inventory: report and database,” Paris: OECD, accessed September 25, 2017, https://www.oecd.org/g20/topics/energy-environment-green-growth/database-climate-fund-inventory.htm. 100 Christine Chow, “Hong Kong joins push for sustainable stock exchanges,” South China Morning Post, September 18, 2015, accessed September 24, 2017, http://www.scmp.com/business/markets/article/1859225/hong-kong-joins-push-sustainable-stock-exchanges. 101 Green Bank Network, “Harnessing Private Investment to Drive the Clean Energy Transition,” accessed September 24, 2017, http://greenbanknetwork.org. 102 International Finance Corporation, World Bank Group, “Sustainable Banking Network,” accessed September 25, 2017, http://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/topics_ext_content/ifc_external_corporate_site/sustainability-at-ifc/company-resources/sustainable-finance/sbn. 103 Heather Lammers, “Industry-backed Best Practices Guides Aim to Lower Financing Costs for Solar Energy Systems,” National Renewable Energy Laboratory, March 31, 2015, accessed September 26, 2017, https://www.nrel.gov/news/press/2015/16486.html. 104 International Capital Market Association, “The Green Bond Principles 2017,” June 2, 2017, accessed September 25, 2017, https://www.icmagroup.org/assets/documents/Regulatory/Green-Bonds/GreenBondsBro-chure-JUNE2017.pdf 105 The Equator Principles Association, accessed September 25, 2017, http://www.equator-principles.com. 106 Luxemburg Stock Exchange, “LGX: A truly green platform,” accessed September 26, 2017, https://www.bourse.lu/lgx. 107 Institute for Market Transformation, “Home Energy Efficiency and Mortgage Risks,” Washington D.C.: Institute for Market Transformation, March 2013, 1-15. 108 UK Green Investment Bank, “Green Investment Handbook: A guide to assessing, monitoring and reporting green impact,” Edinburgh: UK Green Investment Bank Publishing, September 2015, 1-7. 109 The Lab, Driving Sustainable Investment, accessed September 26, 2017, http://climatefinancelab.org. 110 Virgin Earth Challenge, “Removing Greenhouse Gases From the Atmosphere,” accessed September 26, 2017, http://www.virginearth.com. 111 Clean Energy Finance Corporation, “Innovation Fund,” accessed September 26, 2017, https://www.cefc.com.au/where-we-invest/innovation-fund.aspx. 112 Connecticut Green Bank, “New England Hydropower Energizes First Archimedes Screw Turbine site in U.S.,” April 27, 2017, accessed September 26, 2017, http://www.ctgreenbank.com/first-archimedes-screw/. 113 Simon Zadek, “Greening Digital Finance,” International Institute for sustainable Development, January 10, 2017, accessed September 27, 2017, http://sdg.iisd.org/commentary/guest-articles/greening-digital-finance/. 114 United Nations Environment, “Ant Financial app reduces carbon footprint of 200 million Chinese consumers,” Press Release, May 30, 2017, accessed September 27, 2017, http://www.unep.org/newscentre/ant-financial-app-reduces-carbon-footprint-200-million-chinese-consumers. 115 Abundance Investment Ltd, accessed September 27, 2017, https://www.abundanceinvestment.com. 116 Coalition for Green Capital, “Structure & Options for Green Bank Legislation,” Washington DC.: Coalition for Green Capital, accessed September 27, 2017, http://coalitionforgreencapital.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/CGC-Green-Bank-Legislation-Structures-Options.pdf, 1-4. 117 Jeffrey Schub et al., “Green and Resilience Banks: How the Green Investment Bank Model Can Play a Role in Scaling Up Climate Finance in Emerging Markets,” National Resources Defense Council, Coalition for Green Capital and Climate Finance Advisors, November 2016, 1-43. 118 Her Majesty’s Government, “Update on the design of the Green Investment Bank,” London, 2011, accessed September 25, 2017, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/31825/11-917-update-design-green-investment-bank.pdf. 119 OECD, “Green Investment Banks: Innovative Public Financial Institutions Scaling up Private, Low-carbon Investment,” Paris: OECD Environment Policy Paper No. 6, January 2017, 1-15. 120 Future Fund, Australia’s Sovereign Wealth Fund, accessed September 27, 2017, http://www.futurefund.gov.au. 121 Jeffrey Schub et al., “Green and Resilience Banks: How the Green Investment Bank Model Can Play a Role in Scaling Up Climate Finance in Emerging Markets,” National Resources Defense Council, Coalition for Green Capital and Climate Finance Advisors, November 2016, 1-43. 122 Green Climate Fund, “About The Fund,” Republic of Korea, accessed September 27, 2017, http://www.greenclimate.fund/who-we-are/about-the-fund. 123 OECD, “Green Investment Banks: Scaling Up Private Investment in Low-Carbon, Climate-Resilient Infrastructure,” Green Finance and Investment, Paris: OECD Publishing, May 31, 2016, 1-117. 124 Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC), “CEFC Investment Policies,” Sydney: Clean Energy Finance Corporation, 2016, accessed September 27, 2017, http://www.cleanenergyfinancecorp.com.au/media/222517/CEFC-Investment-Policies_161101.pdf, 1-32. 125 The members of the Green Bank Network are CEFC, UK GIB, CT Green Bank, NY Green Bank and GreenTech Malaysia. 126 Energy Resilience Bank, “New Jersey Energy Resilience Bank Grant and Loan Financing Program Guide,” New Jersey: ERB Financing Program Guide, August 8, 2017, 1-25. 127 Green Investment Group, “Helping build green infrastructure in developing countries,” accessed September 28, 2017, http://greeninvestmentgroup.com/funds/international. 128 New York Green Bank, “2016 Business Plan,” Case 13-M-0412, New York: NY Green Bank Publishing, June 27, 2016, 1-36. 129 UK Green Investment Bank, “Annual Report and Accounts 2014-15,” Edinburgh: UK Green Investment Bank Publishing, June 22, 2015, 1-139. 130 Green Bank Network, “Malaysia Green Technology Corporation,” August 16, 2017, accessed September 28, 2017, http://greenbanknetwork.org/malaysia-green-technology-corporation. 131 UK Green Investment Bank, “Annual Report and Accounts 2014-15,” Edinburgh: UK Green Investment Bank Publishing, June 22, 2015, 1-139. 132 Federal Register of Legislation, Australian Government, “Clean Energy Finance Corporation Investment Mandate Direction 2016,” May 5, 2016. 133 Macquarie Group Limited, “Macquarie-led consortium completes acquisition of the Green Investment Bank,” Edinburgh/London, August 18, 2017, accessed September 29, 2017, http://www.macquarie.com/uk/about/newsroom/2017/green-investment-bank.